From the moment I can remember being a kid, I was both competitive and involved in some type of athletics. Until I became too tall, it was gymnastics. Until everyone (myself included) realized I couldn’t catch or throw a ball, it was softball. From middle school on, I was on all the teams. Volleyball, basketball and track (field to be specific) were the final three that lasted through high school.

My identity was very much wrapped up in this athletic life….practice and game schedules, the friends I hung out with, what clothes I wore….all of it really stemmed from what sport I was playing at the time. Although I wasn’t a star by any means, I did find success in specific sports and really appreciated the leadership potential my coaches saw in me.

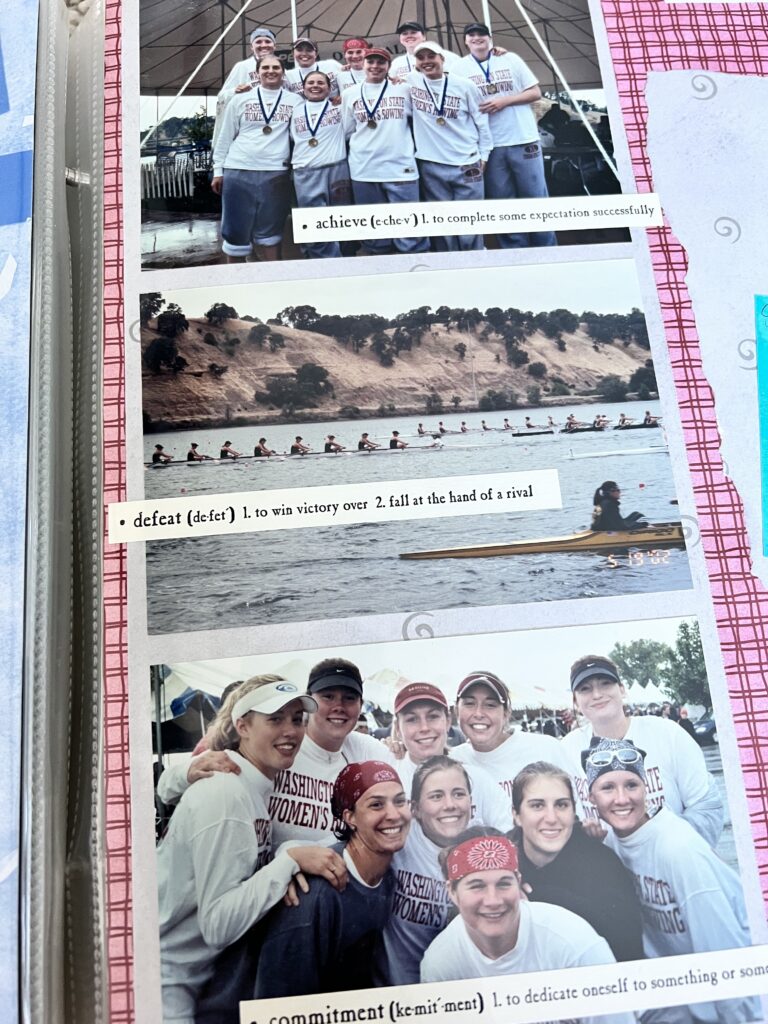

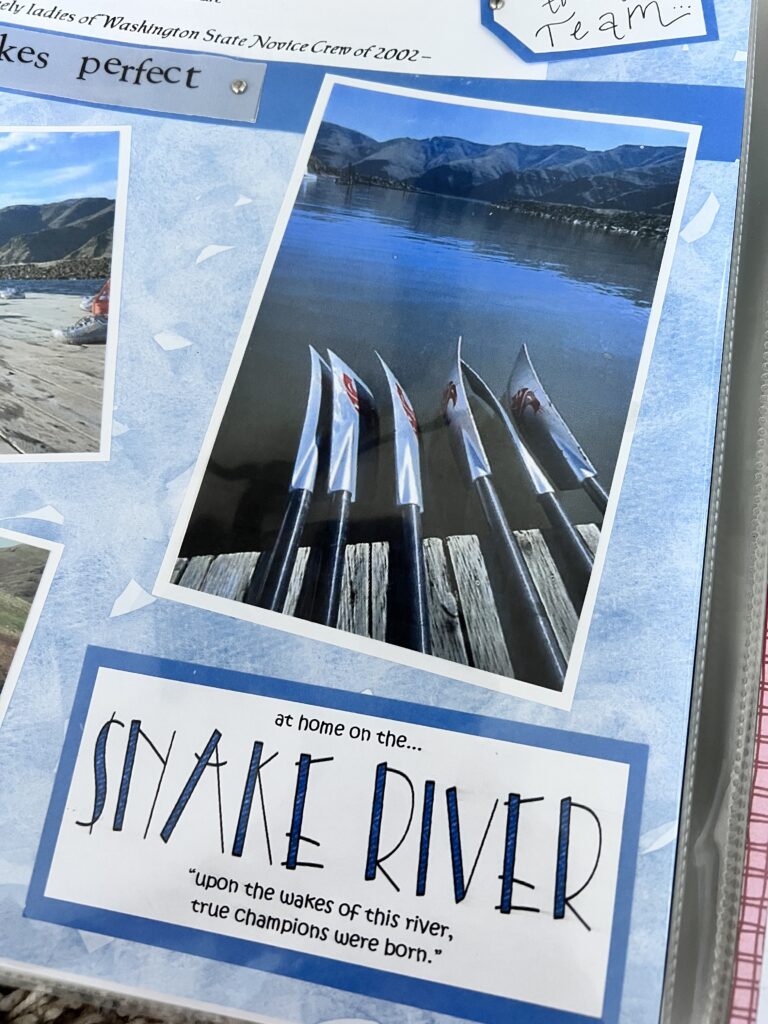

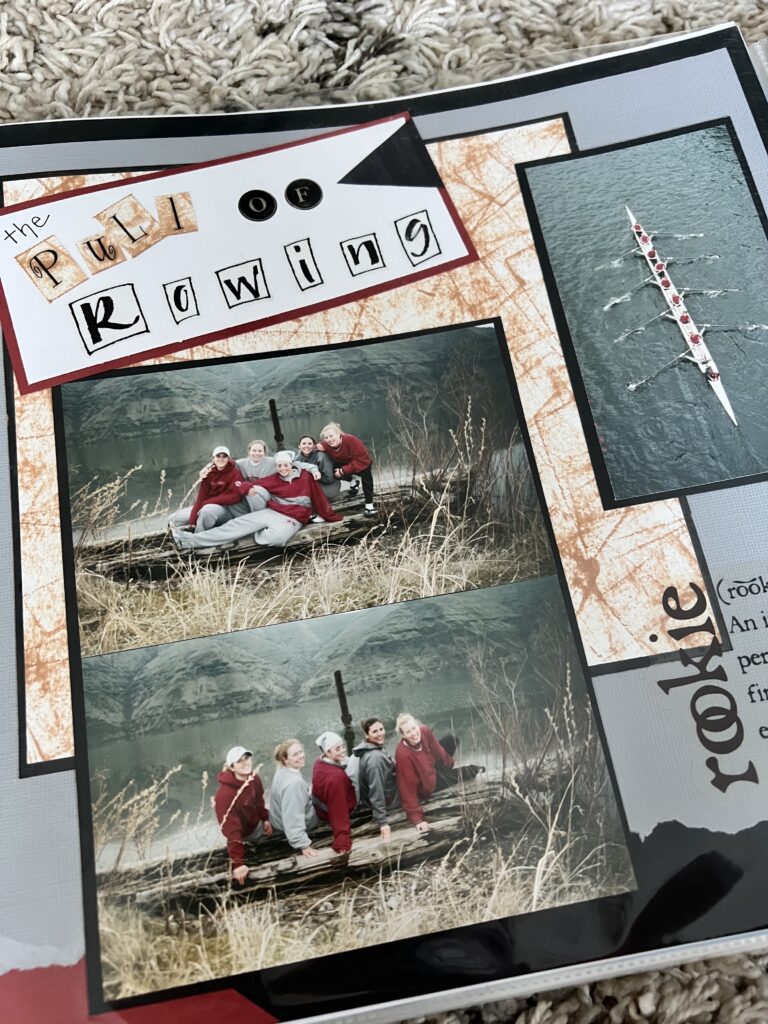

This success led to recruitment from WSU to join the rowing team. Being a D1 athlete was both a privilege (my favorite perk: laundry service!) and a hardship. I felt a lot of pressure to perform and rise above my teammates without any prior experience at the actual sport….and I also wasn’t all that great, which was a hard pill for me to swallow at the time.

After choosing not to continue my crew career and focusing on a job (and let’s be honest, my social life) my sophomore year, I started to struggle. Without the scheduling boundaries, a coach to guide and mentor me, and my body/emotions resetting after going 200% for years – I started to struggle with extreme body dysmorphia and developed an eating disorder that took its toll both physically and emotionally. For me, this looked like restricted dieting and way too many hours exercising at our rec center on campus (even to the point of me going 3 times per day for 1-2 hours at a time).

Eventually, I was able to find a balance for myself but knowing what I know now as a professional, I was definitely experiencing what is now known as post-athlete depression. My struggles with self-worth and my body would continue for years, but ultimately made better by maturity, my own control over exercise and dieting, and my supportive social network.

My own experiences have helped me prepare my own senior athletes for this very transition – many of my players get to go on and play college volleyball. But for others, high school is where their status of “athlete” ends. I encourage them to prepare for that transition mindfully. To think about what body movement brings them joy. To create a schedule that feels good to them and surround themselves with others who love and support them, no matter what they look like, what they eat or what kind of exercise routines they participate in. Just exposing them to the struggle of the transition is more than I had knowledge of at the time and I hope that this critical conversation can help them navigate it more healthier than I did.

To parents of teenage athletes, a few things to remember –

1. Their success in sports will be more tied to their emotional health than their physical health. Which one should you be checking in on more?

2. Let the coach coach. What they need from you is a protective and safe buffer that keeps out the pressure and the competition, not adding more on.

3. Monitor their eating, sleep, mental health closely – do you notice any changes? Extra workouts? Less food at dinner? Avoiding meal times altogether?

4. Talk to them about MORE than just sports…..what are their other interests and hobbies? What else can they do in their summer and free time besides training? Maybe you can do it together!!!

*My parents (and every single coach I had) were incredibly supportive of me as an athlete and did not necessarily do anything to put extra pressure on me – nor do I blame them for any of what I developed in college, as they tried to stay connected and I isolated what information they received. My pressure definitely came from myself and an unnecessary need to compare myself to others. But per usual, I like to use my hard stories for good and for prevention, so by sharing my story, I hope you can be more mindful with your own kiddos or athletes that you mentor.